Cake tester

“Come and help me see that the cake is done,” Elizabeth calls from the kitchen. On the counter is the Dundee fruit cake, just taken out of the oven and still in its tin. She flourishes a curious object that we have laughed over together for so many years, an item that carries a family history.

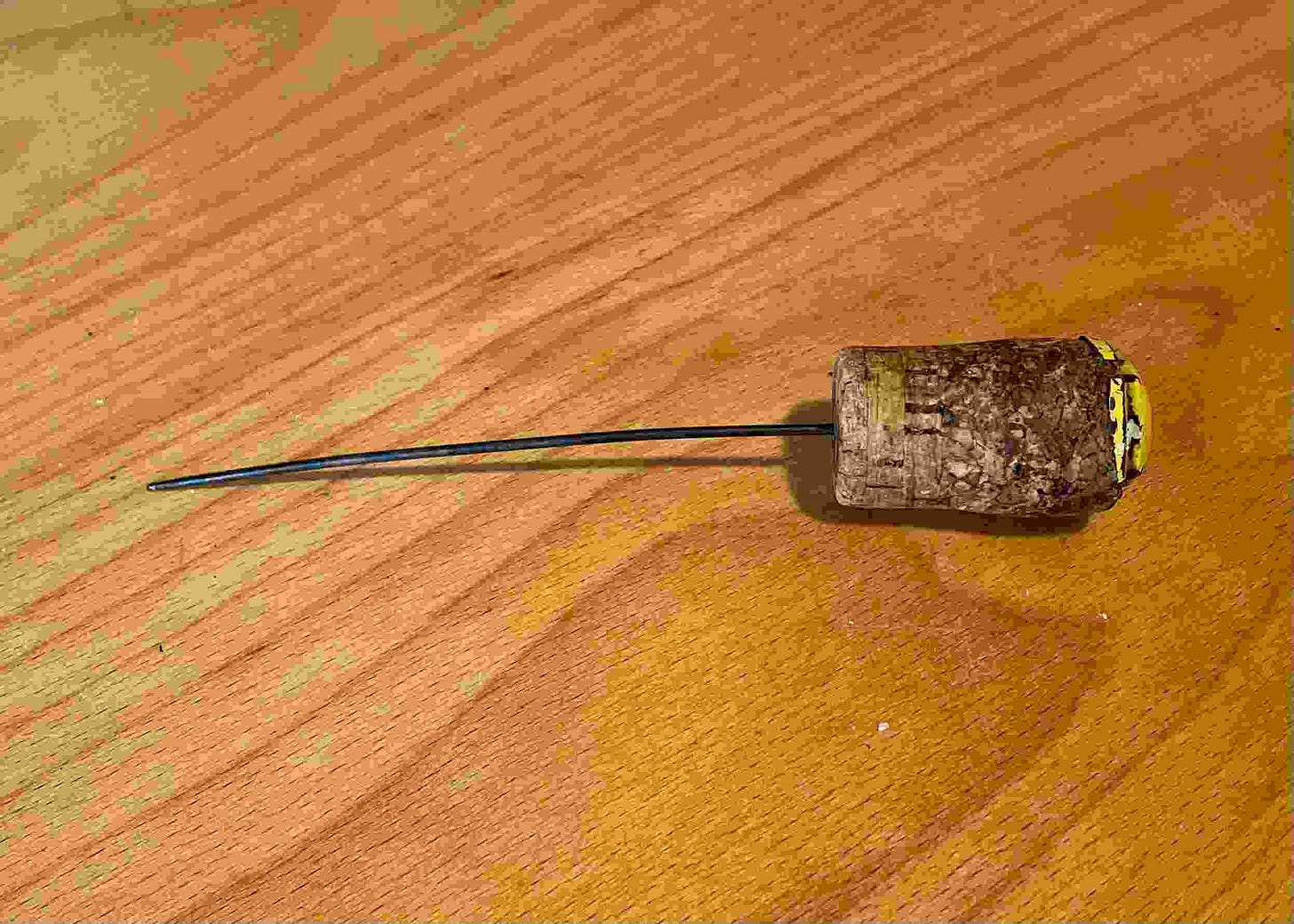

It’s a small gauge, steel, double-ended knitting needle, about six inches long, stuck into a champagne cork. The steel is blackened from many years of use, and slightly bent. The cork is also stained by the many hands that have held it, hands often coated with oil or butter from cooking.

I have been called in because, somehow, I am the expert consultant on whether Dundee cakes are cooked through or not. I hasten to be clear this is not a case of ‘mansplaining’ – I leave cake-making in Elizabeth’s very competent hands. But it is always difficult to be sure that a fruit cake – Dundee, Christmas, or Simnel – is properly cooked in the middle. And since this is the first cake to be cooked in our fancy a new oven, that question is compounded. So I am called in for my opinion.

I take the spike from Elizabeth’s hand and choose a crack between two flaked almonds, near the middle, where the cake batter might still need some cooking time. It slides in smoothly and comes out quite clean. “That’s nicely done,” I say to her, “Lovely cake!” “I have to make what my boy wants”, she replies. Our elder son Ben, his partner Mette, and their son Aske are visiting us this coming weekend.

We look together at the curious object in my hand. “That should be one of your Objects,” she tells me. Of course it should. “It was your mother’s,” she reminds me – her mother would just have taken the cake out of the Aga when she knew it was done without the fuss of testing. “And it’s your mother’s cake tin too, I get much better results with that than any of the new ones I have bought.” The cake tin, like the steel spike, is patinated from many years of use. It leaks ancient grease from the joints when heated, so must be carefully lined with greaseproof paper before the batter is spooned in.

But I don’t think the cake tester was just my mother’s, I think it was my grandmother’s – Nanna’s. Or at least, she had something almost identical. I remember with quite ridiculous clarity, as a small boy of four or five, watching her with Gracie by her side – dear Gracie, who I wrote about in Glass Salt Cellars, had lived and worked with the family since she was about fourteen. It must be the late 1940s. They are standing together in the scullery at Turret Lodge under a single dim lightbulb, next to an ancient gas stove. They too are testing to see if a fruit cake is cooked, just as we are doing in our bright modern kitchen. They seem satisfied with the result, and at that point my memory fades away.

I watched my mother, too, slide the metal spike into her fruit cake, standing in her just post-war kitchen. It was she who explained to me how it worked: if the spike comes out clean, the cake is done, but if uncooked batter is clinging on it needs to be cooked a little longer.

Was she using the same metal spike as Nanna? And is ours the same one? And when and how did it arrive in our house? We can’t quite remember.

Elizabeth’s cake is done. She slides it from the tin, peels off the greaseproof paper, and leaves it to cool on the cake rack. The cake tester is returned to its place in the drawer under the refrigerator, alongside the potato peeler, the zester, and the egg whisk.