These glass salt cellars were gift from Gracie for my 21st birthday. They had little spoons to go with them, that I know Gracie searched out, which have disappeared.

As a very small boy, I was allowed to slip off my chair early during formal sit up tea at my grandmother’s house – we called her Nanna – while the grown-ups continued eating and chatting. Across the big hall at Turret Lodge, I would push open the swing door – panelled on one side and plain on the other – that led into the working domain of the house – the kitchen, scullery, cellar steps, back lavatory, and outhouses where food was stored in those days before refrigerators. Peering round the door, I would see Gracie sitting in a small rundown armchair by the stove, the wide door open and the red hot coals glowing in the grate. She was, of course, expecting me, and would wave me to the hard upright chair opposite her, where I would sit, swinging my short legs in the air, my knees roasting in the glow of the anthracite burning in the grate.

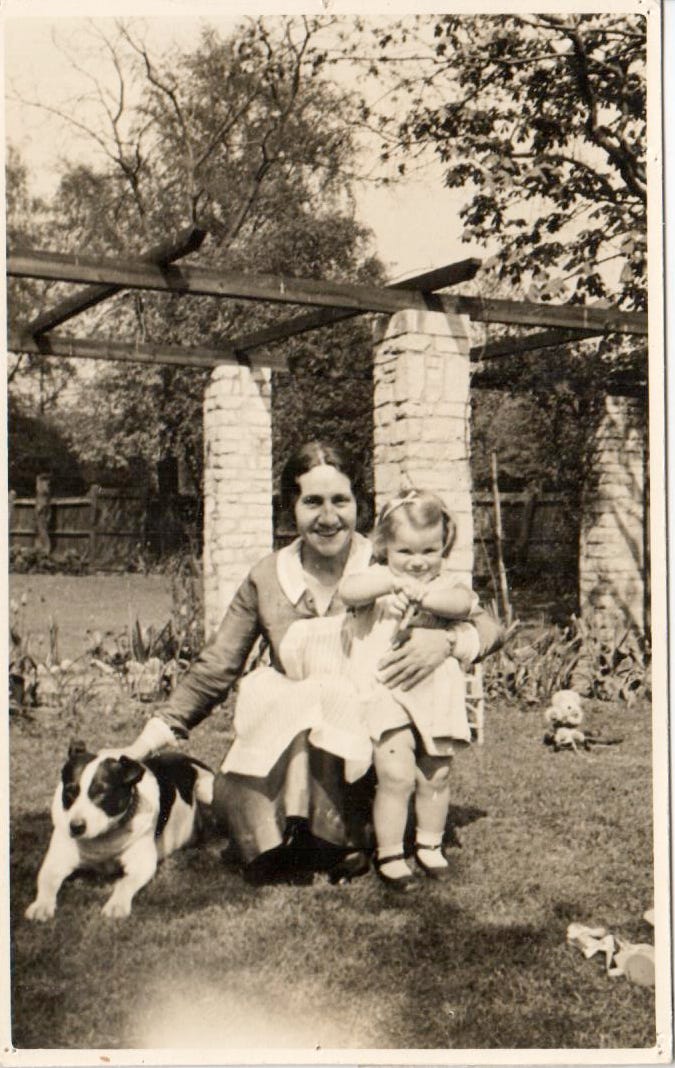

Gracie was of indeterminate age, short, squat, and with bendy legs, a legacy of her undernourished childhood. She told me how, aged about fourteen, she had seen a notice in the local newsagents for a family seeking a live-in servant, and gone round immediately, on her own account, to knock on the door at Thurleigh Road – where my grandmother and family had lived before Turret Lodge. This must have been in the early years of the twentieth century. I never heard Nanna’s side of the story, but I doubt she was expecting to employ an undernourished and poorly educated girl. Gracie explained to me that her grandmother (who had brought her up) was then invited round to Thurleigh Road, so Nanna could make sure everything was above board and agree arrangements for Gracie’s future. And so it was that Gracie came to live with and work for the Whittlestone family, just after Uncle Cyril, the eldest sibling, was born (that’s him behind Gracie in the photo). She stayed for the rest of her life: through the move to Turret Lodge, the birth of my aunt, my mother, and their younger brother, through depression and war, the arrival of the next generation, my grandmother’s decline into dementia and eventual death, after which the family provided her with a flat and a pension for her last years.

I never asked any of the adults about Gracie. It never occurred to me to do so. She had such a fixed place in the household and the wider family: much loved, part of the family and yet somehow not; intimate, yet firmly in her place. She always spoke to my father as ‘Mr Reason’, as my grandmother insisted. As an adult, I put together the pieces to understand that Gracie was probably illegitimate, was brought up by her ‘grandmother’, who she found harsh and punishing, and took the first opportunity she could to get out and find her own life. She was lucky to find my grandmother; she might have done an awful lot worse.

Once I was settled in my chair in the kitchen, we would start our ritual of storytelling. So many times I heard about Gracie knocking on Nanna’s front door and asking for the job. Or Gracie would tell of her china doll, a much-valued possession, unique in her impoverished childhood, that she left in the wrong place on her grandmother’s washing mangle. Her grandmother took in laundry. The mangle was described in detail, sketches scribbled on whatever bit of paper came to hand. I was told how it was kept in the back yard, a huge machine, with an iron framework, stone weights to create the pressure, and a large wheel which was turned the rollers to squeeze the water out of the washing. Somehow the china doll got caught in the mechanism and was smashed. Gracie got no sympathy, told it was all her fault for leaving it in the wrong place. I was, of course, all sympathy for her terrible loss and her horrible grandmother.

At other times, the large tabby tomcat, Tiddles, would leap up on Gracie’s lap and paw her legs – I was always disappointed that Tiddles would never sit on my lap. After a while, he would jump onto the kitchen table and sit next to the tray of Gracie’s tea service. Then the conversation began:

Gracie: What do you want, then?

Tiddles: stares into space and blinks his eyes.

Gracie: Show me what you want.

Tiddles: Looks vaguely in the direction of the milk bottle, sitting half empty on the table with its original tinfoil cap loosely on top.

Gracie: What do you want, then?

This exchange would continue, with me in increasing fits of laughter until:

Tiddles: Reaches out and paws the milk bottle.

Gracie: Take the top off, then...

Tiddles: Stares again into space. If we are lucky, he eventually reaches out and paws the tinfoil cap till it falls off.

Gracie: That’s what you want, is it? So where do you want it?

And again, after interminable questions from Gracie, with me left incapable with laughter, Tiddles eventually paws the teacup in its saucer… By this time I am rocking to and fro in my chair, tears running down my face.

Gracie: There’s a good boy.

And the cat is rewarded with a saucer of milk, which he laps up, still sitting on the table, splashing milk around.

Gracie let me help her with cooking; she knitted woollen coats for my teddy bears; when I was a little older, she took me to the cinema, to the zoo, to the Planetarium near Baker Street Station; and I went down the road each day before school to fetch coal up from the cellar. After my grandmother died, we had a regular date watching Friday night television. And, of course, as I entered my teens and got interested in other things, our relationship faded away somewhat. I say ‘of course’, but I was rather ashamed that I had ‘grown out’ of Gracie and abandoned our childlike relationship. For as I look back, I know that in that kitchen with Gracie I experienced an uncomplicated love and acceptance: it was my place, never occupied by my older siblings; there were no complications, no expectations, no need to assert or prove myself.

Gracie had a happy retirement in a two room flat in Turret Lodge. One, day, when I was at University, I hear she had fallen and broken her hip. Next day, she died. “We are all very upset” my mother wrote to me. My last memory is of the tea reception after her funeral, playing “Roar, roar, I’m a lion!” with my two-year-old niece Sarah, under same the dining table I was allowed to slip down from after tea when I was a small boy.

This is lovely! And so much of it reminds me of my own childhood. We lived in London when I was young (aged 0-6 and 9-10) and my brother and I spent every Christmas and Easter and much of the summer at my grandparents' house in Hampshire. An elderly widow and her companion/servant Alice Fouracre had been evacuated to The White House during the war. By the end of the war, the widow had died, and Alice, brought up in a Barnardo's Home and in service at fourteen, had no family so she stayed on. Her room was on the top floor of this large Georgian house which had both front and back stairs. She did the laundry and some of the cooking and housework, which she shared with my eldest, unmarried, aunt. She had a lively personality and often bickered with Granny, though in fact they were very fond of each other. She used to call my mother "Miss Jean" until she became "Mrs Tony". Alice was tiny; I think I became taller than her when I was about 11 or 12. Alice was part of the household until she began to suffer from dementia and went into the local nursing home. I remember visiting her there; the last time was about 1969. Alas, I have no photos of her. Thank you, Peter, for sharing these memories.